September Macro Matters

Lemon Disco Bisporella citrina

Lemon Disco Bisporella citrina

A higher magnification shot of the individual discs. Photographed at 2.5X.

Late September and October are usually the main months in the Mycologist’s calendar for fungi. They are, without a doubt, a pretty unique and intriguing group of organisms. Over 3000 larger species have been described in the British Isles, and no doubt others are awaiting discovery. Their popularity as photographic subjects has increased significantly in recent times, probably due to the fact that more publications and online websites are now available to help with the identification of some of the more straightforward species. However, spore examination is still the normal procedure for the identification of many others. This field is the domain of an expert rather than the average nature photographer.

It is perhaps fair to say that the majority of fungi are not that colourful and therefore difficult to get excited about? However, having said that there are many, which are, their bizarre shapes and structures make for real eye-catching photographs. The Fly Agaric is perhaps the most widely known British species and is extremely popular with photographers. Others, such as Yellow Stagshorn, Scarlet Elf Cup, Sulphur Tuft and various Earth Stars are equally worth the effort.

Yellow Stagshorn Fungus Calocera viscosa

This is a common and widespread species found on decaying wood. It is often seen growing on old tree stumps. This was a fresh specimen

with virtually no damage; however, the background was a bit chaotic. I photographed it first with a 200mm macro,

but preferred the result with the 300mm, which produced a nice diffused background.

Many larger fungi have intriguing names such as the Penny Bun, Death Cap, Destroying Angel and the vibrant Yellow Brain Fungus, to name but a few. All fungi should be treated with caution; many are highly poisonous, and a few are fatal even if eaten in small quantities. Most people assume that fungi are related to plants – scientifically, they are not? Plants photosynthesize, but fungi do not since they lack the chlorophyll pigment. They also produce spores and not seeds as in plants. The mushroom or toadstool is known as the reproductive part, or fruiting body and is produced from a fine network of cobweb-like threads called mycelium, which exists in the soil.

Penny Bun Boletus edulis

A common and widespread species found in woodlands and often along the marginal edges of paths.

Species can vary considerably in size with some specimens reaching 30cm in width.

My own interest in fungi stems back to my early days as an aspiring macro photographer. A number of my natural history friends were real fungi enthusiasts. I picked up many useful tips and advice from spending time in the field with them. One of the most exciting aspects of fungi photography is the unpredictability of what you might find. Fortunately, the peak season is during the autumn months when most insects and flowers are virtually gone, and the woods and ground vegetation are a suffusion of yellows and browns. Fungi occur in a wide range of habitats, woodland that contains mature populations of birch, beech and oak are generally the most productive. Conifer woodland generally has fewer species, but can still be pretty rewarding especially mature pinewoods. Other habitats worth exploring are coastal dunes, roadside verges and unimproved grassland – the latter is often good for ‘waxcaps’, which appear in a variety of colours. Unlike many other plants and organisms, which appear year after year, fungi are much more unpredictable. Seasonal conditions play an important part in the reproductive behaviour of species, but there is no guarantee that they will appear in the same place each year.

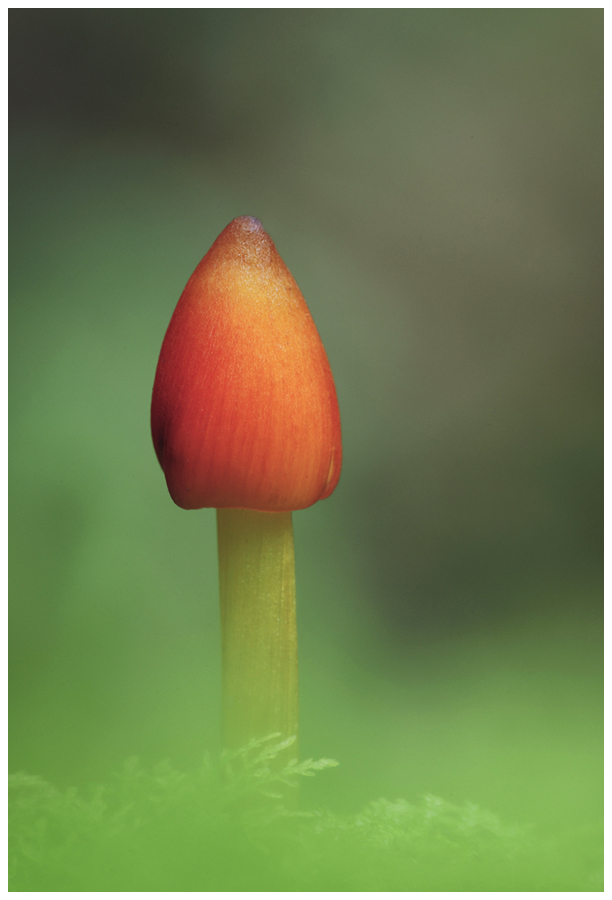

Fibrous Waxcap Hygrocybe intermedia

A very attractive conical waxcap associated with semi-natural grassland.

A warm summer followed by a mild, wet autumn produce the ideal conditions for fungi to flourish. The most productive time photographically is a few days after rain, especially if the temperature and humidity are high – this often stimulates a flush or emergence. Many fungi have a close association with the habitats they occupy and in most cases with a particular host plant or tree. For example, the Fly Agaric has an association with mature birch and pine trees, which means you are more likely to find it where they occur. The fruiting bodies of many species have a relatively short lifespan and start to decay fairly quickly. It is therefore important to photograph them when discovered. Finding perfect examples free from slug damage, even among common species is always a challenge. It can be so frustrating when you come across a really scarce or colourful species only to find on closer examination that it has suffered a slug attack. Despite their so-called lack of speed, they still manage to locate freshly emerged fruiting bodies with amazing rapidity. Some dedicated photographers put a mesh cylinder, or something similar around the specimen to keep the slugs and other creatures at bay and then return when it is fully developed.

Fly Agaric Amanita muscaria

I shoot the vast majority of fungi using natural light. I favour this approach whenever the conditions and the position of the subject allow me to do so. There are a few things to be aware of when working with natural light. If your white balance is set to auto, you can often experience a shift in colour, where the overhead foliage can influence the sensor. As a rule, I set my white balance manually; so all my images have the same colour temperature. This makes it easier to make global adjustments to the images in the software if necessary. Sunlight is another factor to consider as it can cause harsh shadows on the subject and background. These conditions are best dealt with by using fill-in flash or a large diffuser, which softens the light, producing a more balanced appearance. I occasionally use flash as the primary light source when I want a particular lighting effect, also in some situations to darken an untidy background. Switching to manual and altering the ambient-to flash ratio allows the background to appear darker and less obtrusive. I normally position the flash units ‘off camera’, on flexible spikes, which I designed; this allows me to place them in any position I choose. I can also program each unit individually to create a particular effect. Another problem is that many species are often buried among vegetation. As photographers, it is in our nature to tweak things a little to improve the composition or to remove bits of foliage and any other artefacts that may compromise the final appearance of the photograph. This is fine providing it does not involve damage or removal of other plants. However, excessive tweaking can look a bit too obvious and compromise the aesthetics. Be selective, but don’t overdo it!

Many of my images of fungi are shot with a Nikon 200mm macro, but I will also use a 105 macro, 24mm-70mm or the 24mm PCE. These lenses are useful for placing subjects within the context of their environment. When space permits, the 200mm is a more comfortable lens to work with, and the rotating tripod collar allows a smooth transition from horizontal to vertical format without the need to refocus or remove the camera from the tripod head. I occasionally use a 300mm lens in combination with extension tubes when the background is a bit chaotic, and I want to create a very soft look to the image. When photographing fungi you really need a tripod that is capable of working at ground level since many of your subjects will only be a few inches above it. The Novoflex range of tripods (TrioPod-M and PRO75) are modular systems and ideally suited to nature and landscape photography. You have the added advantage of being able to switch legs to what’s best suits your subject.

Brown Birch Bolete Leccinum scabrum

Sometimes the opportunity presents itself and a specimen is in an ideal position for a wide-angle macro image as in the case.

I always look out for species growing in situations where I can show the subject in relation to its habitat.

Novoflex PRO75 with MagicBall Head

Image showing the setup and the Novoflex PRO75 and MagicBall head for photographing this bracket fungus.

It is often known as the weeping polypore due to the honey-like liquid that it secretes.

Oak Bracket Fungus Inototus dryadeus

High magnification image of the amber liquid it exudes from its pores. Photographed 1.5X on Z7 II and Novoflex BALPRO-1 Bellows

and the Novoflexar 60mm bellows lens. This is a very sharp lens ideal for bellows photography.

No longer available from Novoflex but can be found second hand on ebay.

Candlesnuff Fungus Xylaria hypoxylon

What drew my attention to this specimen was the shape and structure of the antlers and the Lemon Disco discs on the base of this small branch.

It turned out to be an interesting pictorial image.

Clustered Bonnet Mycena inclinata

Sometimes you come across when searching, species that grow in situations that make for pictorial compositions as in this case.

Due to the depth of the aperture on the stump, I had to focus stack this image to have sufficient depth of field to keep all of it in focus.

Exposure times can run into seconds, even longer in some situations so working with a remote release is essential. Not all species grow in ideal locations, but it is important to record them as you find them rather than trying to contrive an artificial setting that will be obvious to anyone with knowledge on the subject. I don’t use filters on a regular basis, but a polarizer is useful when it has been raining and helps remove reflections and increases colour saturation. It is also beneficial in bright sunlight and can reduce glare and even out the contrast. Graduated Neutral Density Filters are useful for equalising exposure between the sky and the subject. Describing what constitutes a good composition is often difficult to explain in words. One individual’s opinion on the subject generally differs from another’s. I rely on my experience and judgment, but I believe a discerning eye for the components that form the structure of a successful photograph is much more important. Keep also in mind that no matter how experienced you are with a camera, not every species you photograph is a competition winner – the majority are not, but some species have the potential to be!